Provided by Vicky Gunn, Glasgow School of Art.

Last week witnessed one of those (now less ‘unprecedented’) COVID19 2020-21 moments. On the one hand, the Westminster government gave us a gift: following the independent review of the TEF and the release of the subject pilot evaluation, they abolished the prospect of subject TEF. (Sighs of relief all round). On the other though, they shot two MASSIVE cannonballs straight across the bows of the majestic and diverse pirate ‘fleet’ that is the creative art and design higher education sector in the UK. (Scotland is, of course, different, but what disrupts the sector in England also influences the sector in Scotland). These metaphorical balls are as follows:

- Guidance to Office for Students re: Allocation of Funding

This predates the TEF review outcomes by two days. The key text is located in the Minister for Education’s letter of advice to the Office for Students regarding the allocation of funding: in a simple sentence the state’s financial resourcing of creative arts and designs disciplines is fundamentally reduced. This is achieved through direct guidance that creative disciplines providers within big institutions will no longer get high-cost subject funding. Specialist providers with world leading status become the target of government largesse instead because they are the “providers best equipped to secure positive outcomes for graduates, boosting outcomes for the sector.”[i] Removing the high-cost subject funding will be a death blow for some programmes.

- TEF review response

Secondly, words of chill frame the government’s TEF review response. Going forward institutional TEF needs to be: ‘Better aligning HE to the needs of the labour market and economy’ with an emphasis on outcomes metrics, particularly Graduate Outcomes (GO) and Longitudinal Educational Outcomes (LEO).[ii]

Economic alignment and pirates

2021, then, is already looking to be one of the most transparent statements of creative arts higher education’s apparent fiscal debt to the state to date. The financial outcomes of our graduates are the treasure and now there is data to show where best for a government to invest for subsequent mining purposes.[iii] Make no mistake, GO and LEO ARE about financial outcomes and the prospect of state recuperation of investment and, if you’re sitting in Whitehall, they do not make for easy reading with respect to design and creative arts. They are quite alarming for undergraduate outcomes. For postgraduates, they’re shocking. As the pirates of the sector, we’ve been caught out without a strong enough, influential enough statement of mitigation.

I cannot say I am surprised by this government’s attempts to reduce design and creative arts’ HE provision. They’ve been itching to do it since GO and LEO subject data was available and the cost of art and design programmes in universities just didn’t have enough OBVIOUS tax payback. They didn’t need the TEF for this, they just needed the metrics.

The big institutions are left with the moral (what are the right reasons to keep art and design programmes?) and financial decisions as to whether they can / will continue to ensure the continuation of these programmes with the resourcing needed to maintain high quality studio and technical services provision. When they opt not to, the moral high ground will view this as a failing on the part of the senior leadership in universities (not an under resource in the social contract between the State and the sector). Additionally, students will complain about what they are not getting, and not only will the pirate fleet be diminished, there will be a mutiny from within using the tools of institutional regulation. Quality assurance is about to become much less benign and the Office for Students more, well, forgive the cliché, Orwellian.

So what can we do?

- Improve our conversation about the social contract between state and creative arts and design

If UK HE regulatory systems are just about ‘better aligning HE to the needs of the labour market & economy’, lethargy for articulating subject level impacts locally/ globally as a cultural ‘good’ will continue. This leaves creative arts disciplines especially vulnerable. Metrics embody what is valued. If financial outcomes become the focus, we’ll use energy responding to this & forget the socio-cultural necessity of creative arts disciplines at an HE level. We need to resist that impulse and start to shout about being a driver of cultural confidence and resilience.

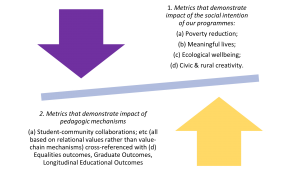

That the State has become so unable to articulate a social contract that embodies the cultural so-what of the disciplines for their communities suggests a design failure in its regulatory systems. We need to challenge this. For example, how different state regulation of HE quality would be with the following types of metrics being the bundle on which we are judged:

For these to have become the new ‘TEF’ indicators, we require a better initial ‘design of the system’ question than the one being used. The same can be said of most quality frameworks in European contexts.

- Rethink the design question behind our regulation

My reflection on the last 12 months of balancing regulatory requirements in the midst of a mismanaged government response to pandemic is that we were already maintaining a system of implied social contract relationships based on nostalgic versions of cooperation between the State and higher education. Moreover, this maintenance was increasingly based on a fantasy of what success was. Fantasy is, of course, an intrinsic part of any social contract, but a fantasy which shores up a nostalgic sense of success has to be challenged.

It is clear that the quality systems of the 1990s-2010s did indicate a success of sorts. Universities and other higher education providers became institutions of the State whilst retaining some autonomy. And the UK HE brand became the gold standard.

But the sector has kept the same underlying design questions for our regulatory systems and tinkered with what is already in place rather than asking the big design question of what should success in art and design higher education look like now? In defining that now ‘success’, we’d be forced to revisit the social contract between the State and our creative disciplines (ie not just the universities as an institution of the state) in a more holistic way. Because, as the allocation of funding letter demonstrates, it’s our disciplines that will see the consequences of outcomes’ metrics.

With the tinkering around our regulatory systems from enhancement-led to outcomes focused and risk-based, a fracture in the actual social contract that has been growing for decades has been obscured. COVID has clarified it. If we want to regulate for quality and excellence in art and design, for example, we need to consider:

a). Values underpinning quality regulations (ie why did it take so long for the quality system to catch up with the fact inequality was being reinscribed at every level of HE? What values did this embody?)

b). Types of information for evaluative judgement of quality: How do we understand & manage the relative decline of qualitative info as key to making decisions about quality with the concomitant rise of numbers? Does this disproportionately harm our disciplines? Can a regulator actually be exemplary in this shift? If so – are they speaking to social designers and what role does quantification of the multiplier effects of creative activities in a community play in mitigating LEO?

c). Quality in the creative arts as defined by the balance of making a life and making a living.

d). Quality as defined by the relational ecology between what our students are learning and practicing and the broader cultural fields with which they interact.

e). How we get creative agency embedded in a regulatory system which has been a trojan horse for:

f). Schoolification of the ‘higher’ in HE creative arts and design;

g). Massification without additional resource Ie whilst the State has lauded our excellence has it also converted us into intellectual factories of efficiency (continuity metrics, really? rather than powerhouses of socio-cultural impact – ie the very essence of the creative arts disciplines, surely?)

- Revalue our quality

If COVID has taught us anything, it’s that a community under pandemic conditions benefits hugely from creative practices. The value of this and the education needed for their flourishing must not be lost in nostalgic fantasies of success whilst government policies are busy fracturing our unique pirate fleet. If the points made above ring true, we need to ask ourselves what value of quality have we been hiding behind? And where, in this, comes a clearly defined relationship between creative disciplines’ knowledge creation, acquisition, and impact on communities local & global through our teaching (that illusive research-practice-teaching conversation)? We need to start explicitly demonstrating the social intentions and impacts of our programmes. And we need to do it quickly.

[i] Guidance to OfS-Allocation of Funding 19th January 2021 https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/media/a3814453-4c28-404a-bf76-490183867d9a/rt-hon-gavin-williamson-cbe-mp-t-grant-ofs-chair-smb.pdf

[ii] TEF review response, 21 January 2021 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-response-to-the-independent-review-of-tef

[iii] Mazzucato, M (2018) The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy, Penguin, p xv. For a broader consideration of this notion of extraction in higher education, see: Gunn, 2019. https://srheblog.com/2019/09/27/notes-from-north-of-the-tweed-valuing-our-values/