Being Bella Baxter

BEING BELLA BAXTER: by Johnny Rodger a clash of worldviews in book and film

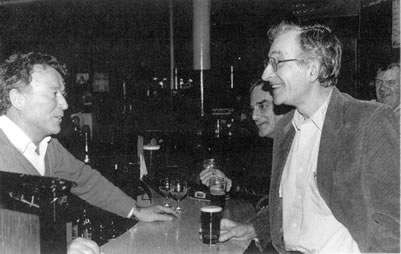

I once spent a week in Paris with Alasdair Gray and Carl MacDougall, another Scottish writer. They were of the same generation, and the best of friends. They performed endless joshing together with funny accents and comedy routines where they rehearsed some clearly long-established mutual roles. I never saw Gray so comfortable in anyone’s company. At one event that week, in discussion of the literature of our hosts, I threw out for debate the opener to Beckett’s early book on Proust. ‘Friendship’, he wrote, ‘is a social expedient, like upholstery or the distribution of garbage buckets.’ Gray shot a fearsome look, and delivered a couple of put-downs about Beckett and his fail-again adopted Parisian misanthropy. The swift and total change in mood was signal, so I thought at the time, of irreconcilable differences in standpoint. It is only recently, decades later, after viewing Lanthimos’ new film, which sets disproportionately much of Gray’s Poor Things in Paris, that the incident came to mind again.

The book

It is hardly the first time that Scottish thought based on socially-orientated positivism and Common Sense has stood its ground against the anti-positivist, individualist and linguistic tradition of French thought which focuses on ‘being’ and the meaning of ‘being’. Scottish Enlightenment philosopher, Thomas Reid, founder of the Common Sense school of philosophy, dismissed Descartes and his Cartesian Doubt of everything that is (including his own existence) as ‘deplorable’, and wrote ‘A man that disbelieves in his own existence is surely as unfit to be reasoned with, as a man that believes he is made of glass.’ Meanwhile Reid’s contemporary, another Enlightenment philosopher, Adam Ferguson, often described as the father of modern sociology, mounted an implicit criticism of Rousseau’s version of the original free individual, the ‘noble savage’, by his insistence on the social origins of humanity. There seems, indeed -in the intellectual sense, at least – to be an Auld Incompatibility, rather than an Auld Alliance, between the two nations.

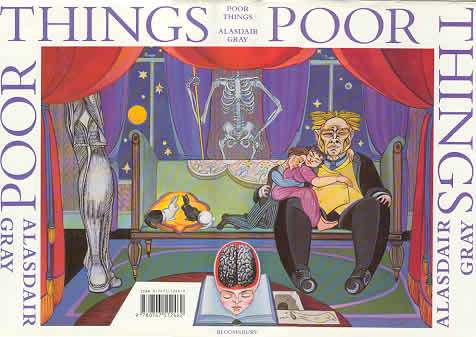

Gray’s novel Poor Things draws heavily on positivist and Common Sense understandings of the human situation and human behaviour. Thus, in a formal sense, we see the ultimate deflation of the most fantastical or surrealist parts of the novel by mundane and everyday notes and references applied via the application of editorial apparatus and supplementary manuscripts to the main text. Gray adds these parts to the novel to contextualise and localize the fantastical proceedings and situate them in realistic and banal human sentiments and behaviours (particularly envy in this case). As such the book’s original crazy and magical elements are brought down to earth with an ironic all-knowing authorial thud à la Cervantes, rather than left liberated, soaring and unhinged from everyday logic as one might find in the works of Garcia Marquez or Jorge Borges. Equally, in the material sense Gray is always ready to supply common sense explanations and patient simplification of complex social phenomena. We see this, for example, put in the voice of cynical character Harry Astley in the clarification of capitalised rubrics in the extensive sections dealing with the education of protagonist Bella Baxter ( eg HISTORY, UNEMPLOYMENT,EMPIRE SELF GOVERNMENT and their proposed remedies by SOCIALISTS, COMMUNISTS, VIOLENT ANARCHISTS or TERRORISTS and PACIFISTS or PEACEFUL ANARCHISTS), and again later, in Bella’s explanation (as a mature woman) of the cause of the World War as a mass suicidal tendency because of the wrong type of motherly love given to male children.

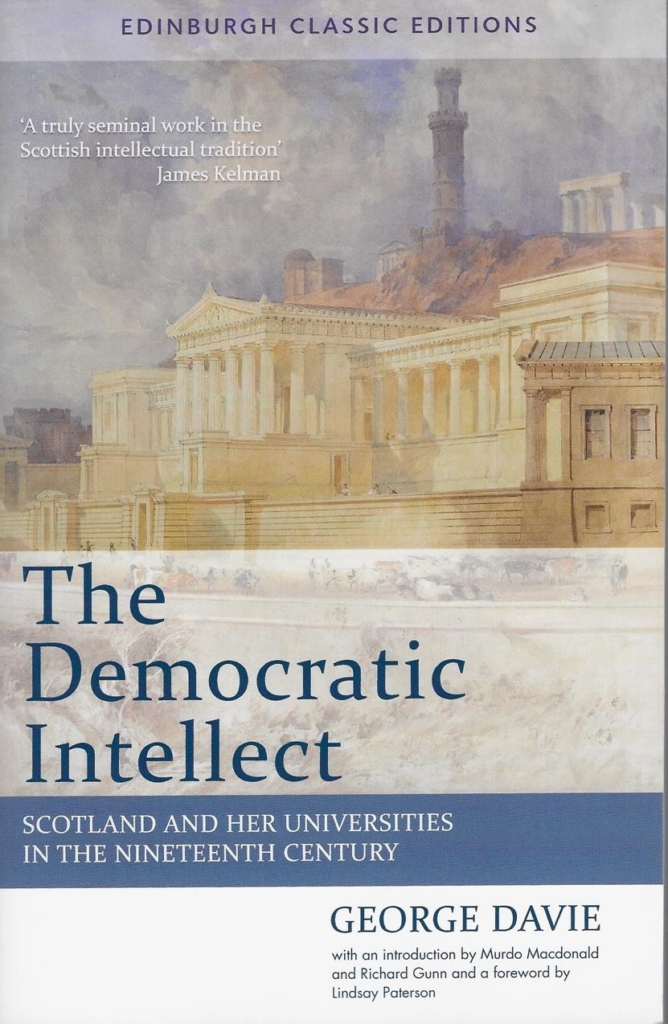

Neither is Gray alone as an artist/writer in modern/late 20th century Scotland in advocating a Common Sense view of the world. His friend, the novelist James Kelman (and also his co-professor in Creative Writing at the University of Glasgow) was just as active in advocating the approach. Kelman penned a foreword to a book of essays on the Scottish Enlightenment by philosopher George Davie (1912-2007), who was arguably the last philosopher representative of the Common Sense tradition. In that introduction, Kelman writes of Davie’s essays on the Common Sense philosophy that he ‘assembles a coherent picture of a continuous intellectual movement in Scotland [i.e. from the 18th century] a genuinely democratic movement.’ Kelman goes on to specify that the movement addresses some basic principles of the social existence of human beings, including the questions:

Do people have the fundamental right to freedom? By what authority does one person, or group of people, control another? Is there a case for assuming responsibility over the social and spiritual life of other adults? When does ‘teaching’ become colonization? Can one culture ever be ‘better’ than another? Is the attempt to deny your right to exploit me ‘unconstitutional’? (The Scottish Enlightenment and Other Essays).

A reading of the book or viewing of the film, Poor Things, would confirm that these are precisely the themes that emerge in the tale of Bella Baxter’s life and her encounters in society with a series of men. Kelman’s reference to the intellectual tradition as ‘democratic’ – apparently taking after Davie’s dubbing of it so, in his most famous book The Democratic Intellect – refers to the accessibility and empowerment offered to everyone through the use of everyday language and concepts, rather than abstruse and elitist philosophical terminology, speculation and argumentation. Hence in one of his essays, Kelman argues that

Everyone can know and everyone can judge. Unless we are mentally ill or in some other way disadvantaged, all of us have the analytical skills and intelligence to attempt an understanding of the world. (And The Judges Said…)

This democratic, anti-elitist and accessible-to-all aspect of the ‘continuous’ Common Sense tradition is shared by Kelman and Gray in their work, though they approach it from evidently different angles and standpoints. Where, for Gray every phenomenon can ultimately be contained in a simple rational explanation (even though that rationalization may be lengthy) – as in the Poor Things examples above of the capitalized HISTORY, UNEMPLOYMENT etc., and the cause of the World War; for Kelman, everyone can understand complex questions and their analyses – like unemployment, colonialization etc., – because in day-to day life everyone already deals with complex questions and situations, for example, managing the budget for a household, or calculating the odds and possible gains or losses on a bet on a horse.

Arguably the most public and open expression of the importance and the continuity of the Common Sense tradition in Scottish life, came with Kelman’s organization of a three day conference in Glasgow in 1990 on the theme of ‘Self Determination and Power’ (see detail here). The conference co-organisers and participants included various left publications and groupings, a broad cross section of Scottish writers (e.g. Tom Leonard and Lorna Waite), artists (e.g. Douglas Gordon and Carol Rhodes), and political activists (e.g. Tommy Gorman, Jeanette McGinn and Cathie Thomson). There was also a substantial international contribution including contingents of Black and Afro-Caribbean radical groups from London (e.g John La Rose and Gus John (who spoke on racism in Scotland) ) and Russian and Lithuanian writers. Alasdair Gray also read at the conference, and significantly, the headline speakers invited by Kelman, and the main interests for many, though not all who attended, were George Davie and Noam Chomsky.

Kelman later described how, while reading a Chomsky work for review he had begun to make connections to the Common Sense tradition and ended up writing to invite him to participate in the conference, ‘The deeper I got into it the more I realized that there were parallels with something else I was reading, which was work by George Davie.’

While the grassroots debates and workshops were undoubtedly the heart of the event, the onstage debate between the then 62-year-old Chomsky and 78-year-old Davie was an intellectual highlight. Chomsky himself later referred to the left, anarchist subversive mix at the conference (it’s not clear if any of this was a reference to George Davie) and said it was ‘the kind of people I take seriously’. It seems that Kelman had correctly identified in Chomsky a congenial spirit to the Common Sense philosophy, particularly as regards its democratic outlook and consequent amenability to inform political and social action, and, indeed, activism. The basis for this congeniality seems to lie in a shared belief in the existence of a basic human nature, and an innate human ability to deal with complex intellectual questions.

It may seem a long way to go about it, but might not consideration of those Common Sense philosophical tenets of a basic human nature and innate intellectual abilities give us insight into Gray’s motives for choosing the Frankensteinian theme of a resuscitated adult body with a surgically implanted baby’s brain as the fantastical core for his novel PoorThings?

In the meanwhile, the notion of Chomsky as a congenial spirit might also provide us with a convenient and accessible mode for laying bare that above mentioned antipathy of Gray and other Scottish writers and thinkers for the French tradition of thought and for exposing the incompatibility of intellectual approaches. For, almost two decades before the ‘Self Determination and Power’ event, Chomsky took part in a debate with the massively influential French post-structuralist thinker, Michel Foucault. The debate of 1971 was filmed and can easily be found on the youtube platform. The discussion between the two is dramatic and intense – not least because it is bilingual – and leads to an impasse, where the respective positions of the two thinkers appear to be mutually irreconcilable: Chomsky discussing the search for social justice that is grounded in the basic universal human nature, and Foucault countering that both justice and human nature are constructs that vary with changing social, political and historical contexts.

Yet, the criticism of those basic philosophical tenets of human nature and innate intellectual ability comes not only from other traditions but also from within the Common Sense school itself. In his book on Scottish philosophy, Gordon Graham writes that after Reid had advocated the Common Sense approach, ‘it soon became apparent that this might result not so much in the resolution of philosophical problems as in the rejection of philosophy’. Indeed, Reid seems sometimes both to anticipate and to encourage this rejection, when at one point he writes ‘I despise philosophy and renounce its guidance: let my soul dwell with Common Sense.’ (in An Inquiry into the Human Mind on The Principles of Common Sense (1764)). The question of the type of ‘soul’ in which the Common Sense approach and analyses dwell seems key at the end of the twentieth century. Does it need the specialized language, procedures and speculation on the nature of ‘being’ when being is a given in Common Sense thinking (the basic human nature)? Is philosophy needed to address those questions Kelman sets out (above) as typical of Common Sense enquiry or indeed, can ‘everyone’ know and judge? If George Davie is often seen as the last late, isolated professional philosopher in a tradition of at least two centuries standing, then the ‘Self Determination and Power’ conference can equally be figured as the moment when an exhausted philosophy passed the Common Sense mantle to the gathered writers, artists and activists, who could arguably bear it with a more appropriately pragmatic spirit into the twenty-first century. And, crowned in particular, as the bearers of this legacy in committed socially engaged writing of fiction, are James Kelman and Alasdair Gray, whose writings are grounded in the economic, political, social, cultural and historical life of one particular place: The City of Glasgow.

Thus the novel Poor Things is set in a particular existing set of buildings in that city, at a particular time period, in engagement with the social formations of that period -British Empire, Industrial Revolution, Late Presbyterianism, Mass Poverty, Social Class Division etc.. The complex form of the novel unrolls, at first, as a late 20th century pastiche of a science fiction Gothic 19th century novel. The fantastic episodes and events of that first text are subsequently reappraised and reframed as a sham by the addition of another text, a letter written by the protagonist Bella (real name Victoria) against whom the violent male fantasies of death, lobotomy and Frankensteinisation were perpetrated. Both these texts are then reframed once again by the addition of the editorial apparatus -the reference notes. In this final text the author, by faking a form of academic research into the case of the two previous texts and beyond, apparently constructs a real-life history of the protagonist Bella/Victoria, mixes it with actual events and historically existing people, and, in effect, retroactively transforms the two former texts, which he claims to have found in manuscript, into addenda to his extended notes, which are a would-be real-life history of the characters. Yet, for any educated person of this society – Glasgow , Scotland – it gradually becomes apparent that this last authorial intervention also presents fictional material. What we consequently understand is that no one single viewpoint is to be trusted fully, and that in such a book, a fictional work engaged concretely with a particular place and a history, or histories, of it, the truth of the social and political era emerges from the repeated viewings, and imagining one’s way into that society from different angles and perspectives. This is, in effect, both fiction’s version of the 18th century Enlightenment technique of conjectural history, and also a literary version, constructed in time, of, and complement to, the polyperspectival constructions of space which Gray makes in his visual art -murals, paintings etc..

The film

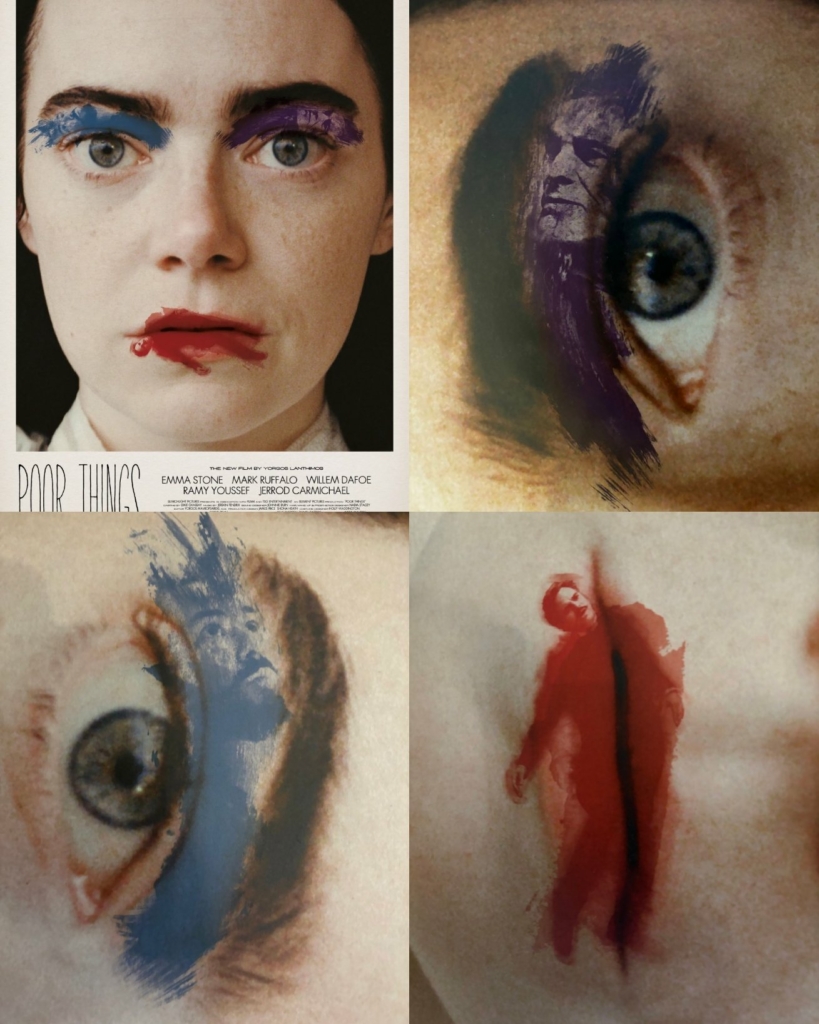

The recently released film of Poor Things, directed by Yorgos Lanthimos, also looks at the story from a number of different angles. All adaptations and translations from one medium to another make changes in the material, and page to screen is no exception. There are things that one can do and do well in a book, and a quite different set of things can be achieved in film. What is immediately noticeable about Lanthimos’s film is the liveliness brought to it by the adoption of an eclectic range of cinematographic styles. In a broadly schematic view of this work we might say that a first part of the film , comprising Bella’s initial residence in the Baxter household, is interspersed with German Expressionist type use of close-ups of the face, chiaroscuro outlining in black and white, and frequent use of diverse shaped framing of the shot (circular, diamond etc.) reminiscent of , for example, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919) and Nosferatu (1922). The scene is thus set as appropriately Gothic in film as the text is in word. A second part, comprising Bella’s trip round the world seems to owe much to the non-naturalistic, highly coloured, eccentric and sexualised hyperrealities such as we see in films by directors Baz Luhrmann (e.g. Moulin Rouge) and Wes Anderson (e.g. Grand Budapest). The eccentric and the bizarre in Bella’s behavior become accentuated in this type of ambience. A final stylistic part, is when Bella’s ex-husband (Blessingham) arrives on the scene, and we are brought down to earth with what seems like a realist, almost documentarian type shooting of scenes as she retreats to a mean, restricted, conventionally upper-class, colonial type residence. Besides these eclectic cinematographic stylisations, there are other aspects which absolutely make the viewing – and listening – a lively experience. The music, composed by Jerskin Fendrix, as a powerful series of emphatically existential howls, magnifies the uniqueness of Bella’s situation in the world, and the adaptation of the original Gray text for screen by Tony McNamara tightens the wit of the dialogue exquisitely, such that the character Wedderburn, a sort of unfortunate poor little rich boy in the book, steps forth as a much more central and contorted cad in the film.

Can we say, then, that the film has at least parity in its cinematic richness with the exuberant literary turns and twists to be found throughout the book? Naturally, for those who have not read the book yet, the film stands and is judged according to taste and its own merits. For everyone else, the two cannot possibly stand together. At the simplest level that is impossible because the filmmakers themselves have chosen to make a film of just one part of the book – the core pastiche gothic tale of Bella’s life as a Frankenstein-type creation- where, as outlined above, Gray has at least two other main component texts which relate both to that story and to each other, place that original gothic tale in different contexts, ironise it and critique it. Lanthimos’s different styles may tell the gothic story of Bella through different lenses, but the tale itself in its fantastic episodes and events is taken at face value. In the book, the text of that tale of Bella’s Frankensteinisation, which the author, or Gray in character as the author, claims to have found in manuscript, is put alongside a letter, purporting to be from the adult Bella, whose real name is Victoria, where she denies that there is any truth in the original gothic text, and writes at one point, that ‘to my nostrils this book stinks of Victorianism. It is as sham gothic as the Scott Monument, Glasgow University, St Pancras station and the Houses of Parliament.’ In his third type of text, as an editor, Gray develops in notes and references a further critique of the Bella as Frankenstein text by inventing whole fictional, but highly plausible lives for Bella/Victoria as an early feminist/political activist and doctor, her first husband Blessingham as a great military officer of the 19th century British Imperial Army, and her second husband as a failed doctor and writer in 19th century and early 20th century Glasgow. The plausibility for these fictional characters are developed by inventing personal histories for them which are entwined in faked relationships with actual historical personalities, institutions and places (Bella/Victoria is shown via presentation of excerpts from texts to have been involved in the Fabian Society, to have known Beatrice Webb, had been written about in the Times, The Telegraph and the Daily Express, and to have corresponded with Hugh MacDiarmid and Patrick Geddes: Blessignham is shown to have been a real British Imperial War hero who was mentioned by the Duke of Wellington, and was subject of poems by Tennyson and Belloc, and written about by Carlyle and Dickens: and the texts of other failed books (besides his gothic tale of Bella) by McCandless are named dismissed by the editor.) Thus, the relationships between the characters in the book become more and more complex as different layers of their being with other people and places in the whole social, political, cultural and historical context of these times are revealed.

The real significance of the film as a portrayal of a stylized version of just one part of the book is that not only is there no Glasgow University gothic spire in it, but there is no St Pancras spire either. That is to say, that the problem for readers of the book is not that the film is not set in Glasgow, but that it is not set in any genuine place. The world in Lanthimos’s film is, to borrow the words of Beckett, ‘social expediency’: it is mere exotic ‘upholstery’ (in its splendid Art Nouveau interiors, its shocking anatomy sessions and its crazy dancing, its hybrid duckdog, goosegoat animals, its exotic and surreal cruiseship and so endlessly on …) to support the consideration, via Bella, of one Cartesian problem: the relationship between mind and body, and the question of identity arising when the two are set at some species of variance via technological (surgical) intervention. That the film has thus been shorn of the social, political and historical range and grounding in time and space we find in Gray’s critical book via a directorial decision to change focus to the isolated question of ‘being’ does not necessarily make it ‘deplorable’. In order to appreciate both book and film at their most vibrant and authentic would it not have been wiser to give the film another, perhaps not unrelated title? – And my suggestion for that, too late alas, is, Being Bella Baxter.

[Editor’s note – readers interested in these issues should also read James Kelman’s essay in Edinburgh Review 84, ‘A Reading from Noam Chomsky and the Scottish Tradition in the Philosophy of Common Sense’]

Useful,interesting + undoubtedly correct piece- film-makers often fillet literary sources for their own ends, that’s natural, but compound,unreliable narrators would be very difficult to convey in cinema, perhaps only capable of being shown in long-form tv series- I enjoyed the film, given the slant the director took from the material.

Thanks for that most interesting article. Spurned me to read my Democratic Intellect and what an inheritace that is not given its proper respect. read the book before seeing the film and enjoyed both. Alisdair’s talent so unique and yet it seems us Scots are reluctant to own our artists and what a treasure trove we deny ourselves.

What a splendid piece!

Yep, there was certainly a creative tension between Enlightenment positivism and its critiques in Alasdair Gray’s epoch. It was framed at the time as an incompatibility between anglophone thinking and the germanophone ‘continental’ tradition, which served to underline British and American exceptionalism and superiority. Much of Gray’s fiction can be read ‘of its time’, as a ‘play’ of this creative tension.

The so-called ‘Scottish’ school of common sense realism (despite the fact that many of its leading advocates were French – it only became ‘Scottish’ after the Edinburgh Tories incorporated it into their Scottish nationalism as part of the UK’s imperial project) first emerged in reaction to the scepticism of the British empiricists, John Locke, George Berkeley, and David Hume, who (following Rene Descartes) cast doubt on our ability to have knowledge of a reality that’s independent of our perception of it (‘esse est percipi’ is the great slogan of British empiricism – [for all non-thinking being] ‘to be is to be perceived’). Against the empiricists, Dugald Stewart, Thomas Reid, William Hamilton, and, latterly, Thomas Carlyle argued from the providential naturalism of the Anglican divine, George Turnbull, that God has providentially arranged for our acts of perception to correspond to mind-independent spatially-located objects of perception, the external reality or ‘nature’ of which we can thus positively ‘know’ through the ‘discipline’ or correct application of our senses.

In Germany, Immanuel Kant proposed a different solution to Hume’s scepticism. Rejecting the providential naturalism of the common sense realists, Kant argued that the presupposition of a transperceptual reality is a necessary condition of our possibly having any knowledge of the world whatsoever and is therefore to be assumed for its pragmatic value in enabling our survival. This had the consequence of making all human knowledge interpretative rather than positive, historical rather than scientific; all reality is an interpretation, everything is ideology. By historicising knowledge in this way, Kant’s critical philosophy and its successors made knowledge possible, but only at the cost of making all human knowledge relative rather than absolute, contingent on our historical perspectives rather than ‘God-like’.

The iconoclasm of critical philosophy and its relativism was blamed by conservatives for the ‘extremism’ and ‘radicalism’ they perceived in the American and French revolutions. In America, the founding fathers seized upon Scottish common sense realism as a stabilising philosophical influence; both Princeton and Yale universities, from which the political establishment of the new republic was drawn, were strongholds of the Scottish Enlightenment and its common sense realism throughout the 19th century. Scottish common sense realism also greatly influenced conservative religious thought and the development of Christian fundamentalism: at Princeton Seminary, theologians built an elaborate fundamentalist system on the basis of a common-sense realism, biblicism, and confessionalism that it imported from Queen’s College, Belfast. Much evangelical theology of the 21st century is based on Princeton theology and is thus a product of common sense realism.

In post-revolutionary France, Victor Cousin and Auguste Comte deployed positivism to moderate the excesses of revolutionary tradition. For much the same reason, conservative common sense realism became the orthodox philosophy of colleges and universities throughout the British Isles until it was supplanted by German idealism in the second half of the 19th century. The German philosophy was at odds with the brittle and atomistic individualism of the Scottish philosophy. On the idealist view, humans are fundamentally social beings in a manner and to a degree not adequately recognised by positivists like Herbert Spencer and John Stuart Mill; it also ascribed a more positive role to the State in contributing to the realisation of value in the lives of individual persons than did the Scottish philosophy.

The Frankensteinian theme at the core of both Alasdair’s and Yorgos’s Poor Things bespeaks this ongoing tension in Western culture between common sense realism and its subsequent critiques, a tension that’s the enactment of a duelling polarity within each work (an ‘antisyzygy’ if you will) that reflects a tension that’s at the heart of late capitalism and its ideological expressions. Both Bellas are children of their times.